Frequently Asked Questions

- The distal regions of the stomach (antrum and pylorus) are most consistently seen in ultrasound. The body usually has a larger air content that may interfere with the exam and the fundus is difficult to access.

- The antral contents are reflective of overall stomach contents.

- The antral size is the least variable and the one that correlates best with gastric volume.

- Use the landmarks (identify liver and aorta/IVC, then focus in the region caudal to the liver and anterior to the vessels.

- Change the patient’s position (supine to right lateral decubitus (RLD)).

- Ask the patient to take a slow deep breath: this may move the transverse colon more caudally bringing the antrum into view.

- Try rotating and tilting the probe.

- In 2-3% of patients the antrum may not be identifiable.

- The stomach has a characteristic thick multi-layered wall. The most prominent layer is the hypoechoic muscularis propriae that is almost always apparent. The colon and small bowel have a thin wall.

- Scanning from right to left can highlight the different stomach areas (pylorus - antrum - body).

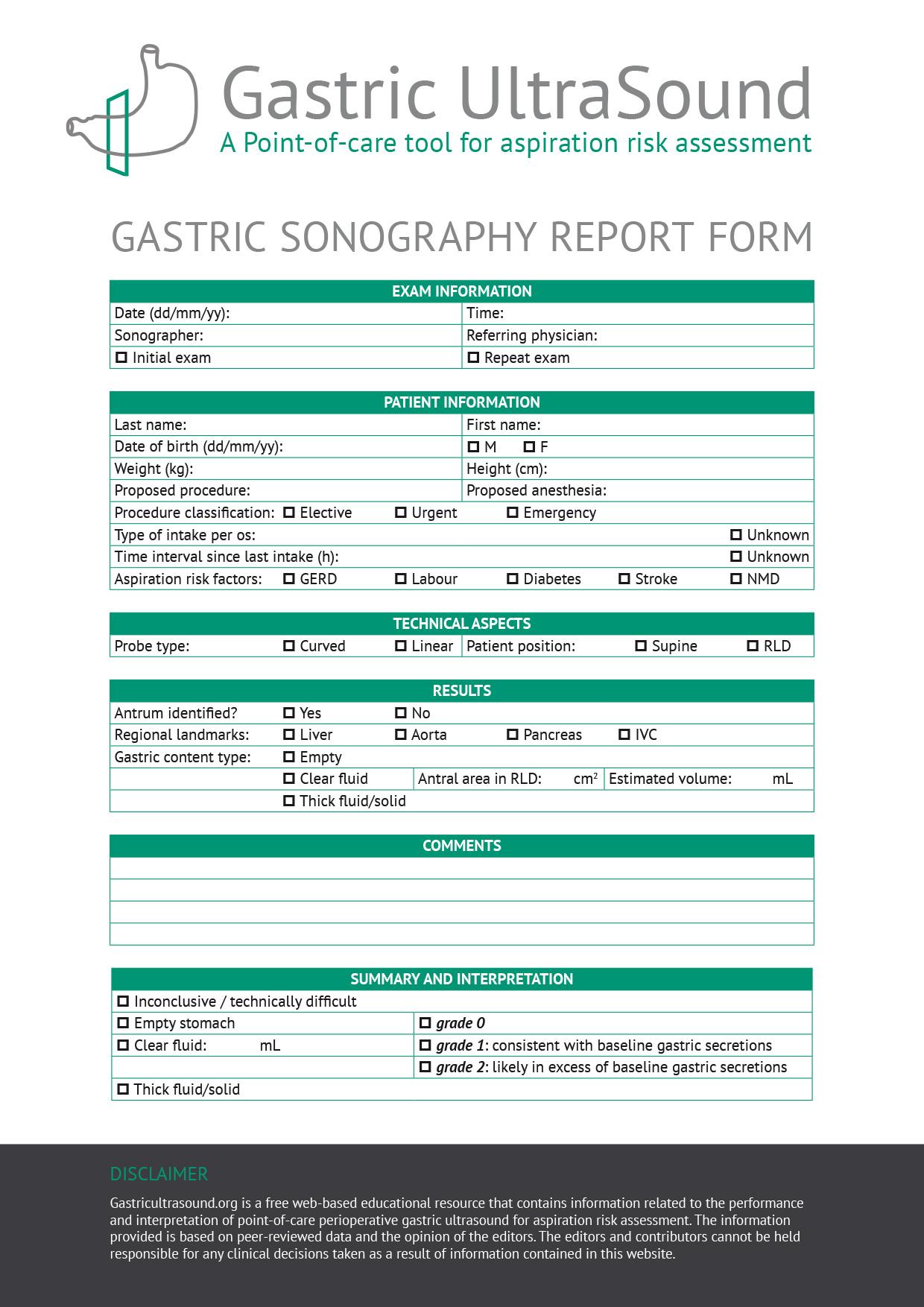

Both the IVC and the Aorta lie posterior to the pylorus and the antrum and both can be identified in the course of the exam. For estimating gastric volume, measuring the antrum (in the RLD) at the level of the aorta is recommended for greater precision.

- The stomach may not be easily found in 2-3% of subjects despite proper scanning technique.

- The findings may not be reliable in subjects with previous gastric surgery (e.g. partial gastrectomy, gastric by-pass) or large hiatus hernias. Volume estimations in particular will likely be inaccurate in these subjects.

Usually less than 5 minutes.

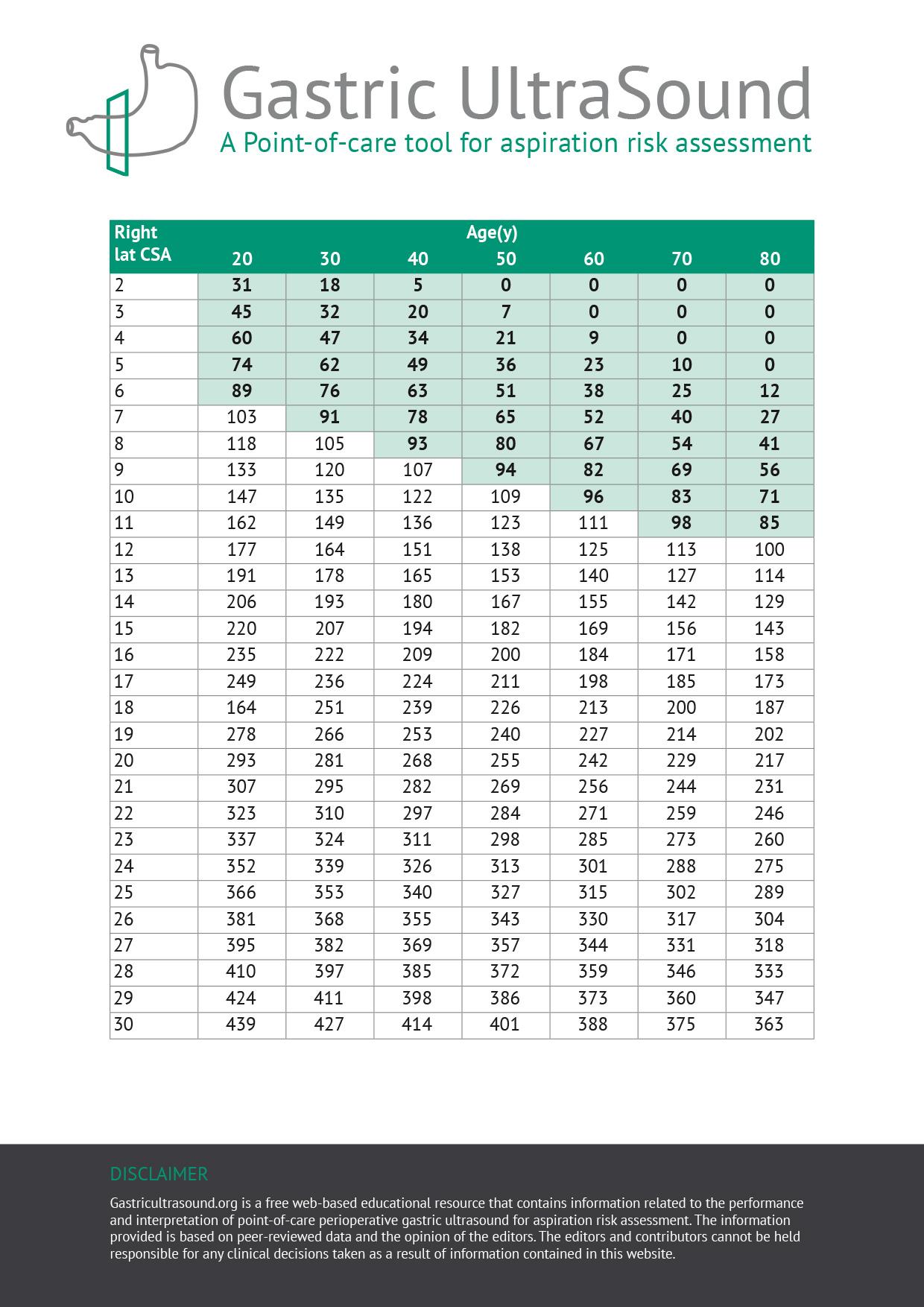

The model presented here has been validated from 0 to 500 mL.

This refers to Total Body Weight.

Volume estimates are highly reliable provided the scanning and measurement technique described are followed systematically.

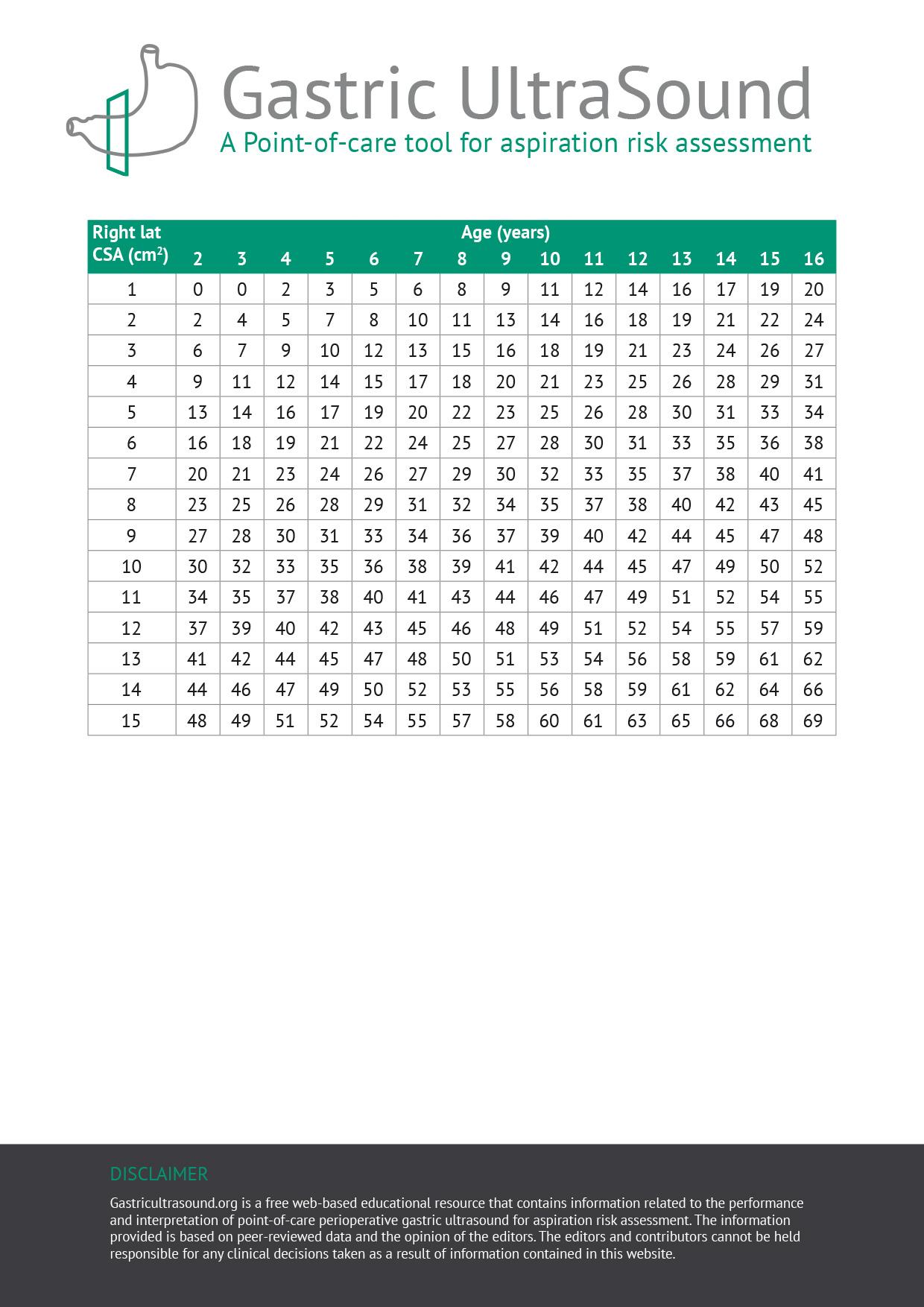

For a given gastric fluid volume, older patients tend to have a higher antral CSA than their younger counterparts. The reason for this observation is unknown; however, it could possibly be explained by a more compliant gastric wall in older patients.

Not necessarily. GERD is a complex disease that affects many parts of the gastrointestinal tract. For example, duodeno-gastric reflux is also common in these patients. So an empty stomach at a given point in time does not guarantee the stomach will remain empty for the duration of the surgery. Therefore, in patients with symptomatic or severe reflux, a conservative approach to management including endotracheal intubation may be warranted.

Although it is easier to visualize the stomach when it’s full, an exam should be considered inconclusive if it is unable to find the organ. This can occur in 2-3% of subjects. One possibility is that it could be “hidden” posterior to the colon. The most prudent approach in this situation is to guide management according to patient history.

Gastric ultrasound is NOT a replacement for fasting guidelines. Fasting guidelines are an important tool for patient safety for healthy subjects undergoing elective procedures. However, for patients with significant comorbidities that can prolong gastric emptying (e.g. diabetes, renal or liver dysfunction, severe neurological disorders) or in urgent surgery, fasting intervals may not be applicable or may be unreliable to ensure an empty stomach. It is in these cases, where gastric PoCUS may be most useful to define gastric content and guide anesthetic and airway management.

This is not recommended. In situations where the pretest probability of a full stomach is either very low (healthy elective fasted patient) or very high (e.g. actively vomiting, known proximal bowel obstruction, ingestion of solids within 2-3 hours), gastric ultrasound will add little to the clinical assessment, and may even “confuse the picture”. Rather, like all other diagnostic tests, gastric ultrasound is most useful in situations of clinical equipoise (i.e. pretest probability of 50%), when gastric content is truly uncertain.

In healthy fasted elective surgical patients, the incidence of a full stomach is extraordinarily low (about 2%). This is likely more common in patients with significant chronic comorbidities. In urgent or emergency situations, fasting intervals are unreliable.

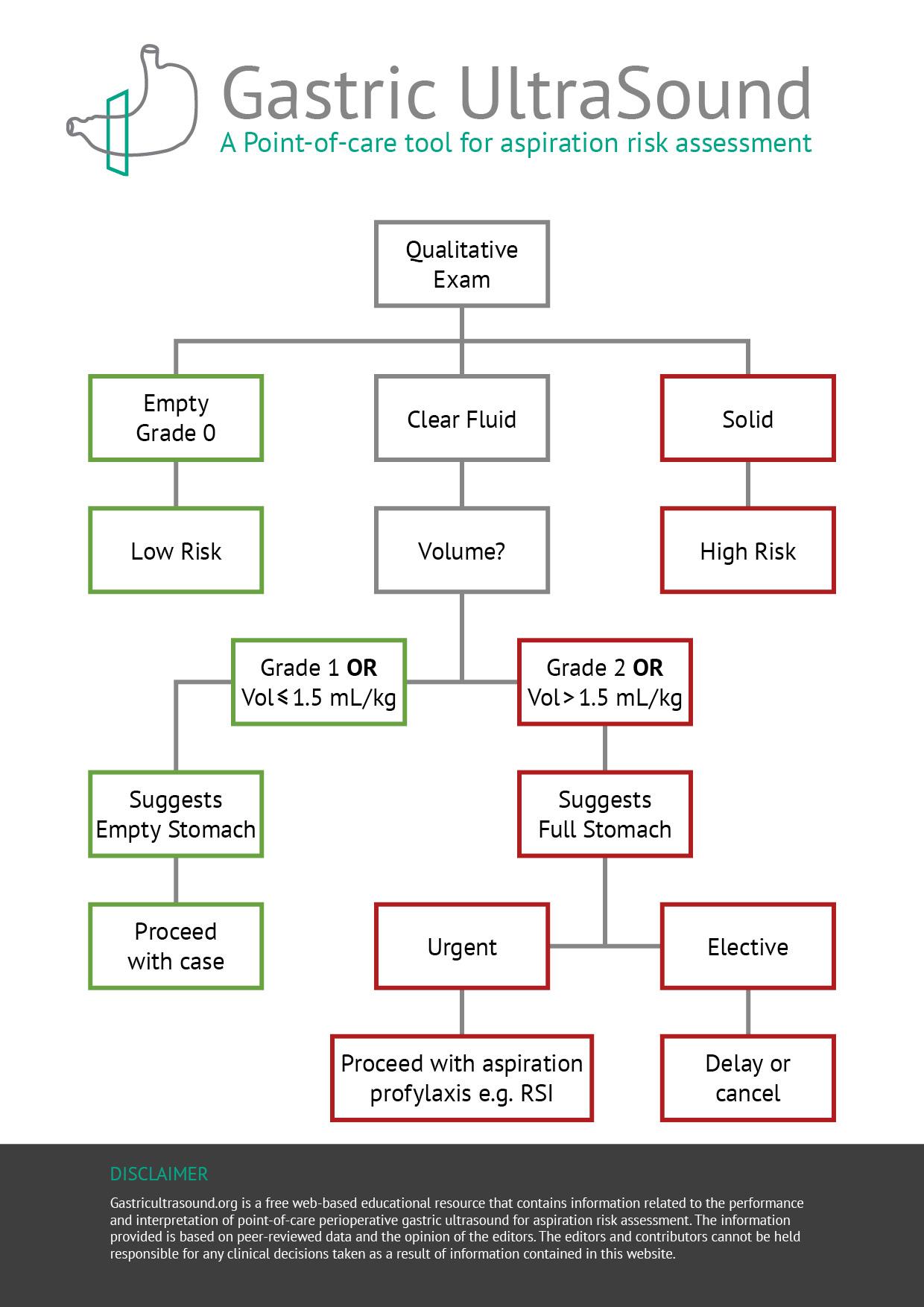

Scanning in the supine position is helpful for two reasons:

1. If solid or thick fluid is observed in the supine position, the stomach can be considered full and the exam complete.

2. Scanning in both supine and the RLD position allows for a semi-quantitative evaluation of volume (grade 0-2).